He started as a name on a list. Then he became a story. After that, he became a ghost.

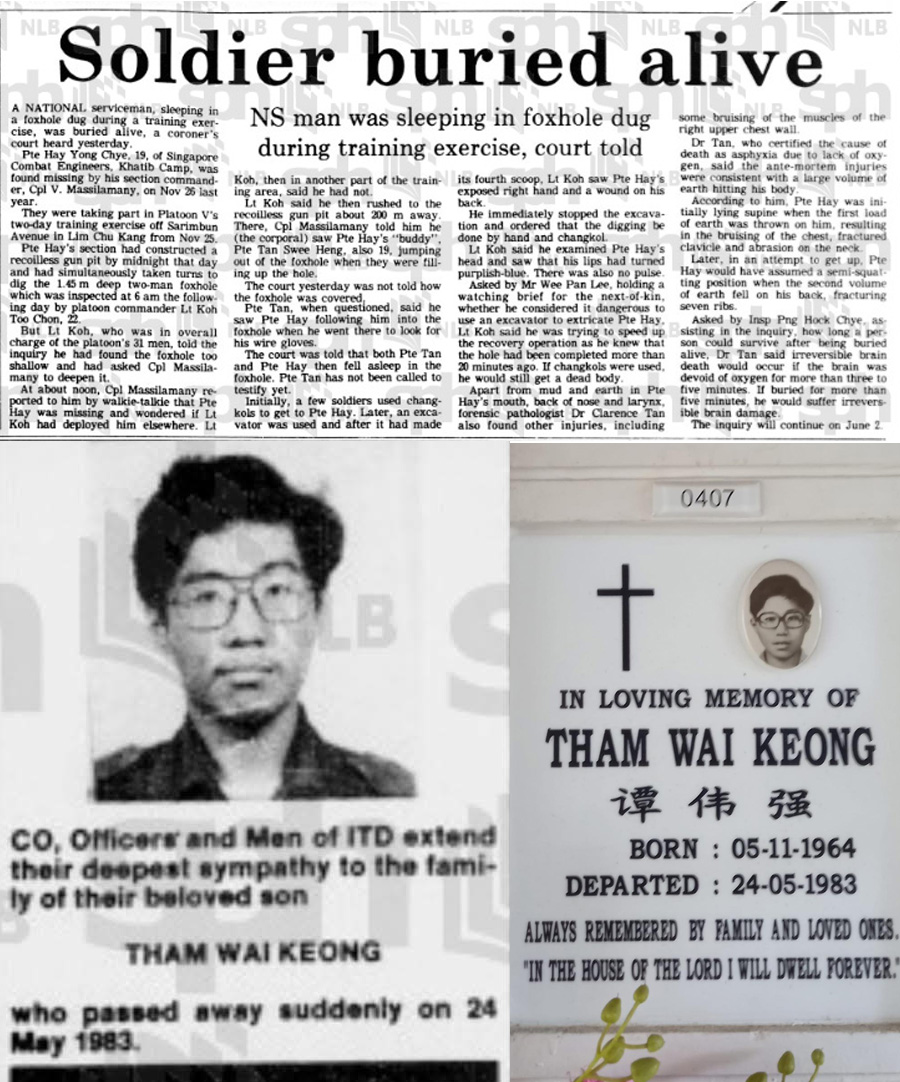

First things first: Tham Wai Keong was a real person. He was born on 5 November 1964 and died on 24 May 1983. He wasn’t “the ghost in the bunk with the third door.” He was a young man who was training at the Infantry Training Depot on Pulau Tekong. But somewhere between reality and rumor, his life turned into legend.

Here’s what actually happened — or at least what online says.

The basic facts (short and blunt)

- Date: 23–24 May 1983.

- Place: Pulau Tekong, during an infantry training route march.

- Found: Dead about 20 metres from the march track, helmet and webbing on, M16 between his legs, muzzle full of mud.

- Nearby: Fullpack and uncapped water bottle in a bush; an entrenching tool (a changkul) lay close by.

- Official finding: Coroner recorded a ruptured stomach and returned an open verdict. Investigators didn’t rule out being struck by an object. No definitive cause like assault or natural illness was established.

So the mystery is real because the verdict was open. The rumor machinery took over from there.

How the story turned into a ghost

After his death, whispers expanded like mould. People love a spooky outline: a recruit who vanishes, a third door in a bunk, gore, suspense. Local papers later ran features calling Pulau Tekong a “place with a dark past,” and the story fit perfectly into playground whispers and late-night bunk tales.

Consequently, small facts were blown up. Details were rearranged. And the man — Tham Wai Keong — got swallowed by the myth.

What likely didn’t happen

Let’s clear the absurd. The idea that he was some mythical ghost trapped behind a bunk’s third door? That’s folklore. The gruesome versions where this becomes a serialized horror script? Also folklore.

Available documents show exhaustion and an unexplained ruptured stomach. There were no clear signs of struggle. The investigators even raised the possibility of blunt-force trauma — possibly from the entrenching tool found nearby — but there was no conclusive proof. Technology in 1983 wasn’t exactly forensic gold. And procedures around safety and tracking during national service were not what they are today.

Why the story got worse over time

People like horror. We retell scary things, and every retelling perks the drama. Also, national service is a shared trauma for many Singaporean men. So when you mix fear, shared experience, and an unexplained death, you get a legend. Tham’s story became a vessel for our anxieties about Tekong: the brutal training, the isolation, the fear of things going very wrong in an environment that felt out of control.

The human cost

Here’s the thing that bothers me: behind every urban legend is a real life. Tham was reportedly one of the stronger recruits — possibly top 10–20% of his cohort — and was training to be an officer. He had family, friends, a future. Instead, decades later, people know only the scary version of his end.

We turned a young man into a lesson in fear. We made his name useful for a scare story. That’s cheap — and a little cruel.

The unanswered questions (still haunting)

- Why was he left behind during a 136-strong route march?

- How did two headcounts fail to catch his absence for hours?

- What happened in that gap between being exhausted at 5 km and being found dead?

- Who was the other man unaccounted for that day? What happened to him?

We might never know. Records from 1983 are thin. Technology for tracking and forensics was basic. People didn’t fight for full transparency like they might today. So we live with that open verdict.

My point of view

Okay, here it is: this isn’t just a spooky yarn. It’s a cautionary example of what collective memory can do. When facts are blurry, stories rush in to fill the void — and they don’t always fill it nicely.

I think three things matter most:

- Remember the person, not the scare. Names matter. Tham Wai Keong deserves to be remembered as a human, not a horror prop.

- Ask for better accountability. If you’re part of a system where people can disappear from a march and be found dead hours later, that system needs better checks. This isn’t about finger-pointing now; it’s about learning so the same mistakes don’t repeat.

- Respect uncertainty without inventing cruelty. Speculation is human. But when speculation turns into cruelty — when a life becomes a cautionary ghost tale — we cross a line.

If anything good can come from this, maybe it’s a sense of humility. We should be careful how we talk about the dead. We owe them that.

What we should do now

- Use his real name when we tell the story. Not “the ghost” — “Tham Wai Keong.”

- If relatives want to talk, let them. Let memory be chosen, not manufactured.

- Learn from the gaps: better safety, better tracking, better headcounts. If nothing else, that’s a practical honor to those who trained and suffered.

Final note

Pulau Tekong will keep its bunk tales. Singapore will keep its folklore. But Tham’s life was not a bedtime story. It was a young life that ended in confusion and left people with questions. Let’s give him the small respect of truth, or at least of not making him a monster in a story he didn’t write.

Rest easy, Tham Wai Keong. You were more than a ghost story.