Yeo Hiap Seng started small: a soy-sauce stall in Fujian in 1900, turned into a Singapore factory by the 1930s. From bottles to canned food to ready-to-drink tea, the company grew into a household name across Asia. Yet, despite decades of wins and clever product moves (hello, Tetra Brik cartons), the company’s biggest threat wasn’t a rival or a lousy product. It was family.

| Item | Info |

|---|---|

| Founded | Started as a soy-sauce business in 1900 by Yeo Keng Lian in Fujian, China. |

| First Singapore factory | The family set up the Yeo Hiap Seng sauce factory in Singapore in the 1930s. |

| Incorporated | Incorporated in Singapore as Yeo Hiap Seng Canning & Sauce Factory on 20 Dec 1955. |

| Listed on SGX | Became a public company around 1968–1969 (sources cite 7 Nov 1968 or 1969). |

| Main products | Makes sauces, canned foods, and non-alcoholic beverages (Asian drinks and teas). |

| Markets | Sells across Asia and other regions; products available in many countries (regional and international distribution). |

| Major takeover | Control passed to the Ng family (Orchard Parade / Far East) after a takeover in the mid-1990s (1995). |

| Current HQ / registered office | Registered office listed at 3 Senoko Way, Singapore 758057. |

| Business today | Operates as a food & beverage company and investment holding group; it also develops property. |

The rise: humble roots, big ambitions

In 1900, Yeo Keng Lian brewed sauces in Fujian. His sons carried the trade to Singapore in the 1930s and set up a proper sauce factory. The strategy was simple: make things locals actually wanted. That meant bottled Hokkien-style sauce, tinned food, and later, drinks aimed at Chinese tastes — a niche the big player, F&N, mostly ignored.

The Straits Times, 5 October 1947, Page 3 (source)

Fast forward: by the 1950s the company was canning curries and bottling soy milk. By the 1960s it was packing soft drinks in Tetra Brik cartons — a first for the region. Then came the listing on the Singapore Exchange in 1969. The Yeos were no longer just a family business. They were a public company with regional reach.

So far, so good. But growth breeds complexity. New markets demand new capital. New capital often means outsiders. And outsiders trigger arguments in families who built things with elbow grease and shared memories.

The pivot: expansion, risk, and a costly gamble

By the 1980s, YHS was not only in food and drinks but also dabbling in property and even U.S. ventures. One big bet was the joint acquisition of Chun King in the U.S. That deal cost them. It lost money. And when money vanishes, so does patience.

Alan Yeo, who steered the company into larger plays, pushed hard for growth. He wanted partners, deals, and faster expansion. Some family members saw this as ambition. Others saw it as risk — and a dilution of family control. Tensions crept in. Meetings became votes. Votes became legal actions.

The family feud: when strategy turned personal

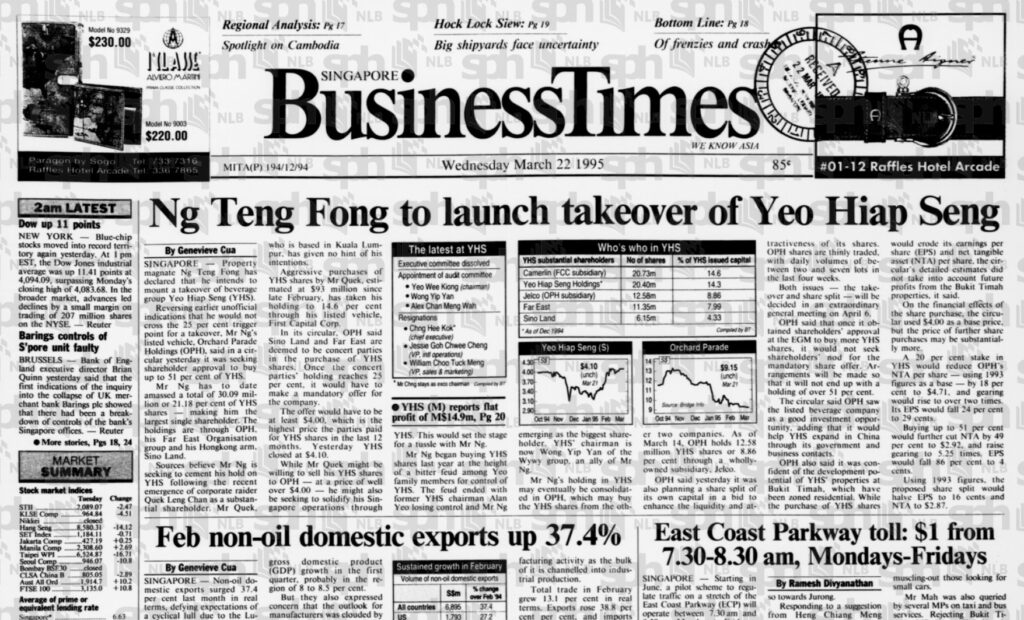

Ng Teng Fong to launch takeover of Yeo Hiap Seng

The Business Times, 22 March 1995, Page 1 (source)

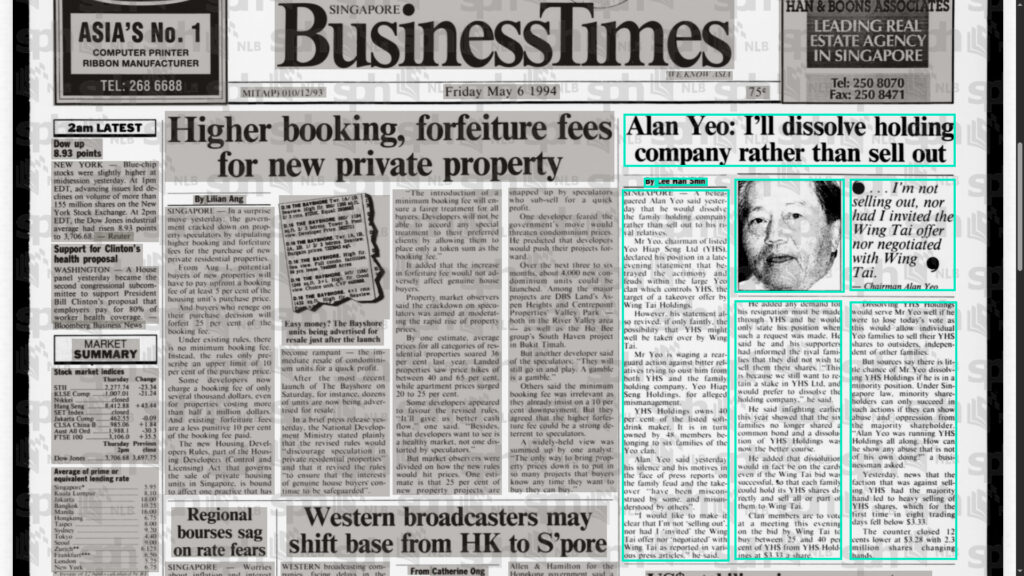

By the early 1990s, the clan was split. Side A supported Alan’s growth plan. Side B wanted to protect the company’s traditional identity and assets — especially land that was suddenly worth a lot more after rezoning. Instead of honest conversations and a clear succession plan, the Yeos drifted toward legal rows. Alan petitioned to dissolve the family holding company. The family block fractured. Shares scattered.

Alan Yeo: I’ll dissolve holding company rather than sell out

The Business Times, 6 May 1994, Page 1 (source)

Once unity cracks, vultures circle. Not literally, but close: property heavyweights noticed YHS’s land in Bukit Timah. With the Yeos divided and their holdings fragmented, buying a controlling stake became doable. Orchard Parade Holdings — backed by Ng Teng Fong’s group — slowly accumulated shares on the open market. By 1995, after a ferocious battle for control, the Ng family emerged the winner.

The Yeos? They walked away from direct control of the brand their ancestors built over almost a century.

After the takeover: brand vs. empire

Under Ng’s control, YHS pivoted further into real estate. The factory moved. The land changed hands. The company kept selling familiar products — beverages people grew up with — but its identity had changed. That familiar nostalgia remained. Yet the empire-style growth and the profitability of earlier decades faded into memory.

The broader lesson: brand loyalty can survive ownership changes. But family control is fragile without clear succession, governance, and communication.

Why this mattered — and why it still does

First, it’s a corporate lesson. Family businesses are different from regular corporations. Emotions, history, and personal pride matter. When those things aren’t handled with structure — clear voting rules, updated constitutions, or independent governance — disputes get ugly and expensive.

Second, it’s a market lesson. Family ownership can be a strength, but in fast-moving markets, access to capital and partners matters. Families that refuse to adapt or that splinter under pressure can lose control quickly.

Finally, it’s a human lesson: money makes people argue. But unresolved conflict, especially about direction and values, can cost a legacy more than market competition ever will.

My take

Look, building something for generations creates deep loyalty. It also creates fragile egos. The Yeo story is classic: a brilliant founding family, great products, then a stretch too far without bringing everyone on the same page. They didn’t just lose control — they lost momentum. That could’ve been avoided with clearer governance and a willingness to compromise sooner.

If a family business asks me for advice (and they should), I’d say: write the rules while trust is high. Formalize roles. Agree on decision thresholds. Make room for outside expertise without treating it like betrayal. And for heaven’s sake, stop confusing family democracy for corporate governance.