You probably think soda began with a red script logo or a fizzy cola commercial. Cute. The truth is messier, older, and somehow way more inventive than the marketing would have you believe. Carbonated drinks didn’t spring fully formed from a 19th-century bottling plant. Instead, they evolved over centuries — from curious chemists trapping “fixed air” in a bowl of water, to pharmacists tinkering with tonics, to multinational companies selling nostalgia in plastic bottles. This is the story of how bubbles went from a scientific oddity to a global obsession, and why your hipster friend’s favourite craft seltzer and that neon holiday soda both owe their existence to people who were basically just playing with chemistry.

TL;DR

- Soda began as a lab experiment by a chemist who infused water with “fixed air” (carbon dioxide) in the 1760s.

- Early commercialization by companies like Schweppes marketed carbonated water as a medicinal tonic.

- The late 19th century saw flavored sodas, including iconic brands like Coca-Cola and Pepsi, turn a pharmacy novelty into a mass-market product.

- Modern trends include craft sodas, hard seltzers, a focus on health and sustainability, and ongoing marketing “wars” between major brands.

The first bubble the world actually noticed

If we trace soda’s family tree, it starts not with cola but with an 18th-century lab accident. In 1767, a British chemist named Joseph Priestley discovered a way to infuse water with what he called “fixed air” — today’s carbon dioxide. He suspended a bowl of water above a fermenting beer vat, captured the gas, and watched as the water took on lively fizz. He wrote about it, and the idea spread: fizzy water was no longer a natural curiosity; it was a repeatable method. (Sparkel)

Within a few decades, the hobbyist tinkering with Priestley’s method turned commercial. Johann Jacob Schweppe — a watchmaker with a fondness for experiments — refined a practical process for making sparkling water and, in 1783, launched a business to bottle and sell it in Geneva. That company, Schweppes, still exists today and is one of the rare consumer brands that can plausibly say, “I was here when bubbles were fashionable for doctors.” (Schweppes, Wikipedia)

Medicinal bubbles: therapy or marketing genius?

Early carbonated water wasn’t marketed as picnic refreshment. It was “medicated water.” Doctors and the public were told that bubbly water could settle the stomach, ease ailments, and generally do what tonics promise: make you feel like modern science is taking care of you. Schweppe and others gave samples to physicians and touted therapeutic benefits. Whether the bubbles actually cured anything is debatable. What’s not debatable is the brilliance of the pitch: make something new, give it medical credibility, and people will buy it.

This is important because it set the template for soda’s future: mix pseudo-science and optimism, then dress it up with a brand and a promise.

Flavour arrives — and with it, the modern soft drink

For decades, carbonated water was the headline act. Then flavoring stepped onto the stage. The 19th century saw a slow carnival of flavored effervescence: lemonades, tonics, and ginger ales. Schweppes, for instance, introduced flavored versions of its sparkling water, and later developed ginger ale and tonic water — beverages that went on to have careers of their own. By the mid- to late-1800s, flavored fizzy drinks were gaining momentum and moving out of the pharmacy and into soda fountains and parlor bottles. (Schweppes)

Now imagine a pharmacist in a small American town: he mixes sugar, syrup, plant extracts, and carbonated water, offers a sample at his counter, and sells a “tonic.” That’s the basic origin story of several household names.

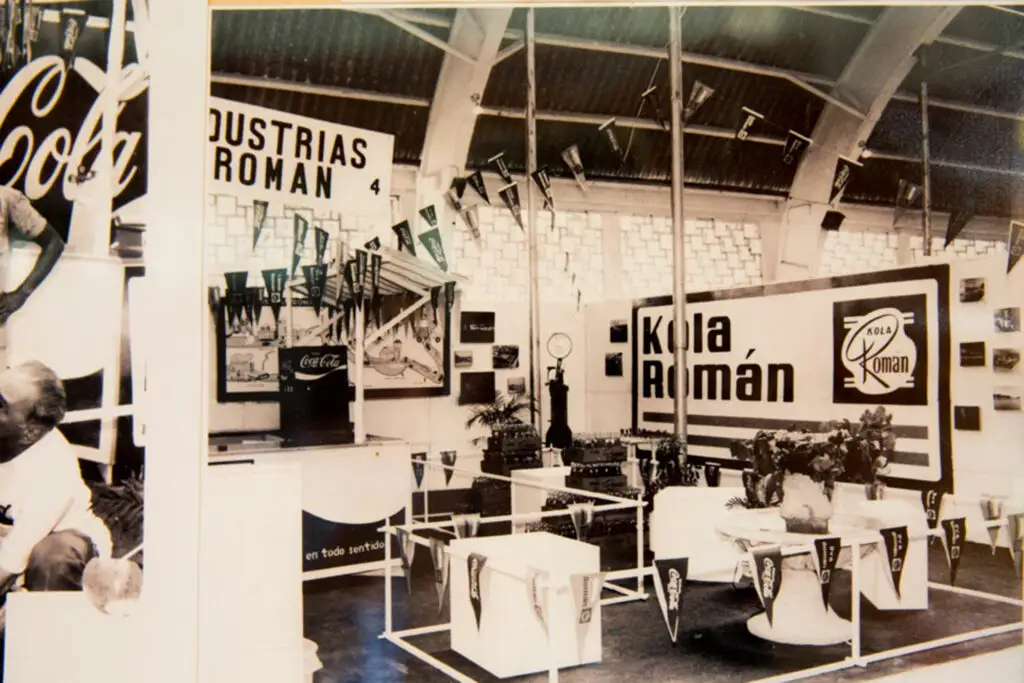

Kola Román — the South American claim to an older soda crown

Here’s a twist that ruins a neat, cola-centric origin myth: long before Coca-Cola or Pepsi, a soda called Kola Román was reportedly being made and sold in Cartagena, Colombia, from about 1865. The backstory is colourful: a local entrepreneur brought soda-making equipment back from a trip to London and created a kola-style beverage that found favour along the Caribbean coast. In some local histories, Kola Román is celebrated as one of the oldest marketed sodas — predating many drinks that get more global press. If you care about national firsts and underdog claims, this one is delicious. (Al Día News)

Why haven’t you heard this in your pop culture trivia? Because the global cola narrative was co-opted by American brands that went on to dominate international markets and mass media. But regional histories matter. Kola Román is a reminder that soda’s evolution wasn’t centrally planned in Atlanta or New York; it happened wherever enterprising people decided to sell a bottle of sparkle.

Coca-Cola and Pepsi — the soda stars arrive

Still, it would be dishonest to skip the giants. Coca-Cola arrived on the scene in 1886, when Dr. John Stith Pemberton sold a syrup mixed with carbonated water at a pharmacy in Atlanta. It began as yet another medicinal tonic — Pemberton’s experiment to treat headaches and fatigue — but a simple formula, a memorable name, and particularly effective branding turned it into an avalanche. By the early 20th century Coca-Cola had become a cultural symbol in the United States and, increasingly, worldwide.

Pepsi’s origin story is equally small-town: in 1893, pharmacist Caleb Bradham was serving a soda fountain concoction called “Brad’s Drink.” By 1898, seeking a catchier, more marketable name, he rebranded it “Pepsi-Cola,” borrowing from the notion that his drink aided digestion (a nod to “pepsin” and dyspepsia). What followed was a century of strategic pivots, bottling innovations, and an advertising war that would define modern marketing.

Bottling and keeping the fizz: a technological race

It’s one thing to make bubbly water in a lab; it’s another to bottle it and deliver fizz to the masses. Stronger glass, better closures, and manufacturing scale changed the game. Over the 19th century, bottling technology evolved such that carbonated liquids could stay under pressure and travel without losing all their personality. That technological step made soda a retail product rather than a fountain novelty. The result? Distribution exploded. Bottled soda made it into stores, doorsteps, trains, and eventually, airplanes. The logistics of keeping fizz alive essentially built a modern consumer category out of a laboratory curiosity.

The tonic and the mixer: gin’s best friend

While colas grabbed the headlines, other carbonated drinks found niche but enduring roles. Tonic water, developed in the 19th century using quinine, became popular among British colonial communities for its supposed anti-malaria properties — and later as a mixer for gin. Ginger ale became a standard for settling upset stomachs and for mixing with spirits. These drinks show soda’s flexibility: it could be medicine, refreshment, or the supporting act for an alcoholic star.

Schweppes, originally a seltzer company, pivoted to ginger ale and tonic water and thus anchored itself in both the medicinal and cocktail cultures of the 19th and 20th centuries. (Schweppes)

The 20th century: mass markets, advertising, and the soda wars

Once bottling and distribution were solved, the rest was marketing. Soda companies poured creativity and budgets into advertising. They sponsored radio shows, painted water towers, and later flooded TV with jingles and celebrity endorsements. The early-to-mid 20th century was the era when brand identities hardened: Coca-Cola with its classic script and holiday campaigns; Pepsi positioning itself as the youthful alternative. Advertising didn’t just sell taste; it sold identity. To drink this brand meant you were part of something — patriotic, youthful, modern, or trendy depending on the era and campaign.

This period also saw fierce competition over recipes, bottling rights, and market share. The “soda wars” were real, combining legal battles, creative marketing, and global expansion. Brands became symbols of national power and cultural reach. It’s no accident that fast food, film, and soda success stories often ride in the same chestnut horse of globalization.

Limited editions, holiday sodas, and the cult of novelty

Fast forward to more recent decades and you see another trick: scarcity and novelty. Companies learned they could spark renewed interest by offering limited-time flavours, holiday packaging, or regionally exclusive variants. That’s how a seasonal “peppermint cola” or a “pumpkin spice soda” can make social feeds light up. This tactic is twofold: collectors chase rare cans and shoppers fall into urgency-driven buying. It’s clever, slightly manipulative, and wildly effective.

The health pivot: sugar, regulation, and the era of shame

By the late 20th and early 21st centuries, the public conversation shifted. Soda’s sugar content became a political and public health target. Studies linking sugary drinks to obesity and diabetes led to soda taxes in multiple cities, warning labels, and ever more aggressive calls to reduce consumption. The industry responded in predictable ways: reformulations (diet sodas), smaller portion sizes, and more marketing around “zero sugar” variants.

Diet sodas addressed calorie concerns but introduced controversies of their own. Artificial sweeteners offered a lower-calorie aspirin for guilt, but questions about long-term health impacts and taste fidelity persisted. For many, the substitution felt like a compromise: less sugar, but also less soul.

Rebels with a cause: craft soda and independence

When a mass market becomes guilty, a counterculture springs up. Enter craft sodas: small producers experimenting with real cane sugar, botanical infusions, and heirloom soda fountains. These brands lean into authenticity and transparency: real ingredients, artisanal production, and Instagram-ready labels. Their success isn’t just about taste; it’s a reaction against plasticized, hyper-marketed soda. People began to buy soda as they buy coffee: for provenance, story, and distinctive flavour.

Bubbles meet booze: hard seltzer and hybrid drinks

The 2010s introduced a new category that blurred the lines: hard seltzers. Seeing the seltzer resurgence, alcohol companies added a buzz and birthed light, flavored alcoholic seltzers that exploded in popularity. They combined the low-calorie promise with simplicity and convenience. Suddenly, seltzer wasn’t just an alternative for soda-shy people; it was a mainstream alcohol category transforming bar menus and backyard parties.

Packaging and the planet: why the can matters now

Soda’s packaging evolution is a quiet ecological saga. Glass bottles were the initial standard; then came aluminium cans and PET plastic for convenience and cost. Now sustainability concerns make packaging a hot topic. Recycling rates, single-use plastics, carbon footprint, and refill schemes are reshaping how fizzy drinks are made and sold. Consumers care not just what’s in the can, but how that can got made and whether it will haunt a beach in 2030. Brands are slowly responding with recycled materials, lighter cans, and even refillable bottle programs in select markets.

Globalisation, local flavours, and culinary crossovers

Soda brands adapted to local tastes as they spread. Global giants translated campaigns, but smaller regional sodas kept their cultural identity. In Japan, limited edition flavours cater to local palettes; in Colombia, Kola Román preserves a nostalgic regional spot. In other markets, cola blends were combined with tea, or fruit syrups were added to create unique soft-drink traditions. Soda became a culinary item as much as a convenience item, integrated into festivals, local rituals, and everyday dining.

Science: what makes a soda sing?

Let’s be nerdy for a paragraph because the science is part of the magic. Carbon dioxide dissolves into water under pressure. When the pressure drops (you open the bottle), the gas comes out of solution as bubbles. Those bubbles aren’t just aesthetics; they carry aroma molecules to your nose and provide a distinctive mouthfeel — the tiny tingles that our brains have learned to associate with refreshment. Sugars, acids, and flavour oils bind to those bubbles and influence how quickly they pop and how the drink’s taste profile evolves as it warms. Small changes in production — syrup concentration, CO₂ volume, temperature — ripple into significant changes in perceived quality.

Why soda still matters culturally

Beyond taste, soda is a cultural signal. Think of the soda fountain in old films or the modern craft soda that declares taste credentials. Brands anchor memories — birthday parties, road trips, family dinners. They occupy social spaces: stadiums, movie theaters, vending machines. Even as the market fragments, soda still performs the same social function: it’s a shared, instantly recognizable treat.

The future: personalization, botanicals, and tech

What’s next? Expect more personalization. Just as coffee shifted to pour-over and single-origin obsession, soda’s next wave may focus on botanicals, terroir, and customization — mixes tailored for health goals or micro-regions. Technology may allow on-demand carbonation at home with better flavor cartridges or low-waste refill systems that combine the convenience of a fridge staple with the sustainability of reusable bottles.

Brands will also continue to experiment with hybrid formats: probiotic sodas, CBD-infused options (where legal), and functional sodas marketed for sleep or energy. Regulatory frameworks and public health pressure will shape how aggressively companies pursue sweet formulas. In short: expect variety, a dash of guilt management, and plenty of packaging innovation.

My point of view (yes, here’s the opinionated bit)

Soda’s history is a lesson in marketing, chemistry, and culture. It proves that an invention can be both trivial and transformative. Carbonation itself was a lab curiosity; it became a commodity because people learned to sell ideas — health, joy, identity — wrapped in bubbles.

Here’s the frank take: the industry is good at two things — invention and reinvention. When public health pressure increases, companies pivot to “better for you” formats. When novelty stalls, they create scarcity or regional exclusives. And when markets fragment, they acquire the indie brands and repurpose their authenticity for mass audiences. That isn’t inherently evil. It’s effective business. But the cost is that taste and tradition often get commodified and flattened on a global production line.

Personally? I love the theatrics of the soda story. From Priestley’s accidental bowl experiment to Cartagena’s colonial entrepreneurs to the billboard wars between colas — it reads like social history with a sugary glue. I’m not apologizing for liking a good ginger ale anymore than I’ll apologize for appreciating a beautifully engineered ad campaign. But I also believe consumers can be savvier. Demand transparency: fewer empty promises like “natural flavours” with no explanation, and more accountability on sugar, packaging, and health claims.

If you want my shopping advice: try local or craft sodas for flavor adventures, use classic colas sparingly as a ritual, and for everyday hydration, let water hold court. Soda should be occasional joy, not background habit.

Quick timeline

- 1767 — Joseph Priestley documents a method to infuse water with carbon dioxide.

- 1783 — Jacob (Johann Jacob) Schweppe founds his company in Geneva to commercialize carbonated water.

- 1865 — Kola Román reportedly begins production in Cartagena, Colombia — an early marketed soda with regional fame.

- 1886 — Dr. John Stith Pemberton serves the first Coca-Cola in Atlanta.

- 1893 / 1898 — Caleb Bradham sells “Brad’s Drink” (1893) and later renames it Pepsi-Cola (1898).

Final fizz: what to take away

Soda didn’t start with a brand battle between two giants. It started with curiosity and got hijacked — in the best way — by marketing and manufacturing. From medicinal bubbly to global icon, soda evolved because people loved novelty, taste, and story. Today the landscape is more diverse than ever: massive brands shoulder history and distribution muscle, while craft labels push flavour boundaries and sustainability schemes challenge the old order.

So next time you pop a can, think about the long chain behind that little hiss — chemistry, eccentricity, colonial trade routes, and a century of advertising. It’s more than sugar and bubbles. It’s modern history in a carbonated capsule.